NEILL’S PRELIMINARY SKETCHES OF OZ

Of the nearly 4,000 finished illustrations John R. Neill drew for the Oz book series, less than 10 percent are known to survive.

Of the nearly 4,000 finished illustrations John R. Neill drew for the Oz book series, less than 10 percent are known to survive.

Perhaps surprisingly, most of what does survive is from Neill’s earliest work on the series. Of the 13 novels Neill illustrated for original Oz book author L. Frank Baum, at least one piece of finished artwork is known to exist for 8 titles.

Conversely, of the 19 Oz books Neill illustrated for Baum’s successor, Ruth Plumly Thompson, only 5 books have known finished examples. Sadly, this means many of the most vibrant drawings (and the most colorful characters) Neill drafted for the Oz books may have been lost to time. John R. Neill’s family retained none of the final artwork Neill created for the Oz book series (all was turned over to the publisher upon completion) but they did retain many of Neill’s preliminary pencil sketches.

Happily, much of Neill’s preliminary Oz sketches are for characters and books for which no final artwork is known to survive, and they give us a rare glimpse into Neill’s process, and of the creation of some of the most beloved creatures in the Oz book universe.

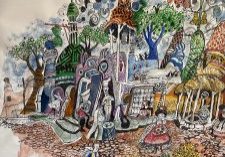

Neill’s assignment of illustrating the Oz books was often a fast task, and there are frequent stories of his having received the finished manuscript so late, he had less than a month’s time to complete the final drawings before publication deadline. At the top of the blog is an image Neill composed for “Anything of Oz,” an anxious attempt to begin work on the yet to be received manuscript of THE GIANT HORSE OF OZ (1928). But Neill’s imagination was readily accessible, and he often began sketching ideas right on the typed manuscripts as he first read them, as exampled by Neill’s copy of the manuscript for SPEEDY IN OZ (1934) now housed at the San Francisco Public Library.

John R. Neill was an illustrator who frequently used models to capture expression and anatomy. And it’s easy to imagine that Neill may have sketched in real time – perhaps even members of his own family as inspiration – for an early design of King Randy of Regalia and Planetty, the name sake of THE SILVER PRINCESS OF OZ (1938).

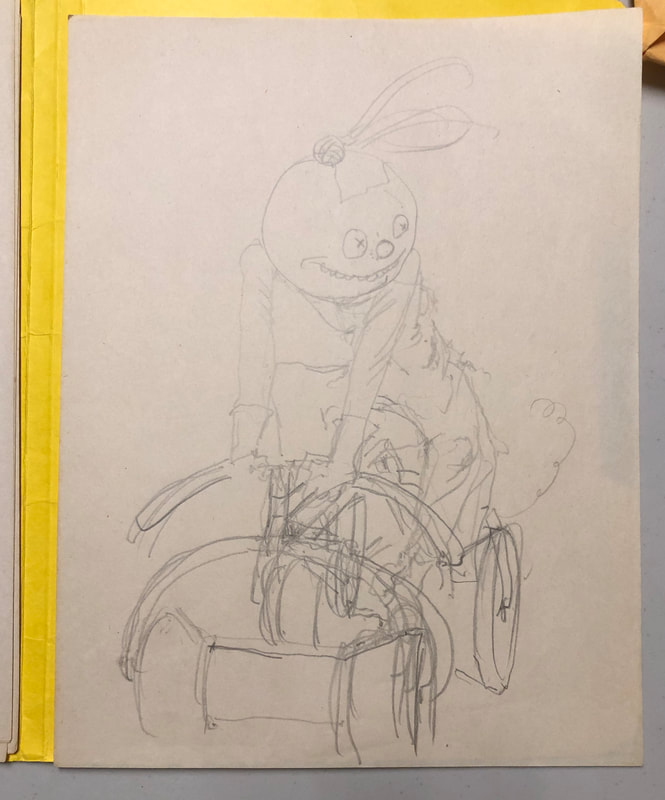

It’s equally understandable that often Neill’s surviving preliminary sketches are for creatures that don’t exist outside the worlds of fantasy. A particularly delightful example are those he drew for a seven armed shepherdess named “Handy Mandy,” one of the most whimsical characters in the entire series. On two pages, Neill attempts to sort out the details of how such a creature would navigate every day movements: running, jumping, pointing, lifting. Perhaps so tickled by his findings, the sketches became the basis for the endpapers of the final book, HANDY MANDY IN OZ (1937) and an inspired introduction for the reader into her unusal world.

The only surviving sketches from OJO OF OZ (1933) are for the character Snufferbux the Bear, and they detail another recurring theme in Neill’s preliminary sketches – how to make the ordinary, “extraordinary.” Back to anatomy, Neill seems to first want to master the realistic stance of the animal, then slowly embellishing and animating to create a non human character who speaks and dances. Similar sketches exist for other animals in the Oz universe, and they echo Neill’s desire to first satisfy realism before turning to fantasy.

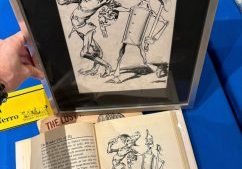

John R. Neill’s finished pen and ink illustrations for the Oz books were usually done on Bristol board. In 1909, while drafting his work on Baum’s THE ROAD TO OZ, Neill used one side of the board for rough pencil sketches and the other for a final drawing (usually of a different scene in the book). Some of the most fun surviving examples of these are Neill’s early renderings of what Jack Pumpkinhead’s pumpkin house might be, and what the anatomy of the Shaggy Man’s head emerging from water might look like.

The last surviving examples of Neill’s preparatory sketches are from 1943 for a book Neill wrote called THE RUNAWAY IN OZ. Neill created an extensive collection of pencil drawings for his ideas of how characters and scenes might look. Sadly, Neill died before the book could be edited or the illustrations finalized. In 1995, Neill’s manuscript was revised and illustrated by Eric Shanower, who used Neill’s rough sketches as inspiration for his final drawings.

Special thanks to Michael Patrick Hearn for insights and David Maxine, Jory Neill Mason, Bill Campbell and The Oz Enthusiast Blog, The International Wizard of Oz Club, Robert Schmidt, and the San Francisco Public Library for images included in this blog.