NEILL OR NOT?

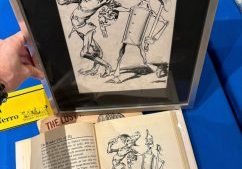

As originally printed in 1904, two John R. Neill illustrations for The Marvelous Land of Oz

On the quest to uncover the surviving original artwork drawn for the Oz book series, The Marvelous Land of Oz remains tantalizing. Published four years after The Wonderful Wizard of Oz, this first Oz sequel was an enormous success in 1904. Surviving photographs pasted in L. Frank Baum’s personal family scrapbooks reveal not only the extensive advertising blitz that surrounded the book’s release, but that the original pen and ink artwork drawn by John R. Neill to generate the illustrations in the book were showcased in elaborate promotional displays in department store windows.

The handful of surviving artworks from Land are also some of the earliest found in private collections. Oz author, Jack Snow was one of the first major collectors to seek out original illustration boards from the Oz books, which hitherto had mostly been considered just utilitarian parts of the printing process.

But faced with financial hardship, Snow sold the bulk of his Oz collection to rare book dealer Howard S. Mott, who in quick turn re-sold three pieces to Columbia University in 1955. In an earlier blog, The Lost Art of Oz examines one of these illustration boards in the Columbia archives that is an anomaly: an original pen and ink drawing that correlates to a drawing in The Marvelous Land of Oz, but that is resized and eliminates the central character of the Wogglebug from the illustration.

A recent discovery at the University of Virginia offered a similarly intriguing variant. Described in the school’s library catalogue as an original pen and ink drawing by John R. Neill, published with the caption “The Wood Steed Gave One Final Leap,” a xeroxed file copy provided by the library staff revealed some eyebrow-raising irregularities. The illustration itself is cut – nearly by a third- and more quizzically, the legs of the Sawhorse crudely redrawn to be thicker than in the drawing as it appears in the book.

Could this, indeed, be John R. Neill’s original pen and ink board from 1904? If so, why the alterations? And would Neill himself have been the one making the changes to his own work?

Could this, indeed, be John R. Neill’s original pen and ink board from 1904? If so, why the alterations? And would Neill himself have been the one making the changes to his own work?

Luckily, a spirited investigation by Penny White, reference librarian at UVA, along with insightful findings by the incomparable ‘Royal Researcher of Oz,” Michael Patrick Hearn provides us with some answers – not only about the drawing at UVA, but as it turns out, also the mystery illustration at Columbia.

In 1918, the George Matthew Adams Service, a prominent newspaper syndicate offered a serialization of The Marvelous Land of Oz in weekly installments, under the title “The Wonderful Stories of Oz.” Archival images of newspaper sheets reveal that both variant drawings were, in fact, reprinted in the Adams Service feature.

Taking into account the needs and specifications of recreating an image on a newspaper page, alterations, like the truncations made to the original “The Wood Steed Gave One Final Leap” illustration, begin to make sense. To a lesser degree too, it’s easy to imagine why certain details, like the legs of the sawhorse, might be changed to be more visible when printed as a smaller image.

But if the mystery about ‘what’ the modified illustrations were intended for was finally solved, other questions remained. Were these revised drawings Neill’s original artwork, and would he really have done such modifications himself?

As it turns out, in both instances, the answer is likely no.

Closer examination (and scanning) of the drawing at UVA reveals that the image in their library is, in all probability, a modified printer’s proof, with the revised horse legs drawn over corrective paint.

Closer examination (and scanning) of the drawing at UVA reveals that the image in their library is, in all probability, a modified printer’s proof, with the revised horse legs drawn over corrective paint.

Oftentimes, proofs are also retouched by hand with dark ink, so it’s not unusual for them to be mistakenly identified and catalogued as an original pen and ink drawing, even by experienced researchers.

In contrast, the drawing at Columbia is, indeed, an actual pen and ink drawing, but when we take into account the obstacle of resizing the original illustration in the book from horizontal to square, it seems the illustration may have simply been redrawn to fit the specifications for newsprint.

As for Neill potentially drawing the revised illustration himself, while the image is a close copy, Neill’s grand-daughter, Jory Mason, herself an accomplished artist, is quick to point out, “In my opinion, the illustration does not look like his line work.” The revision also lack’s Neill’s signature from the original – likely another tell-tale sign it was instead the work of a skilled in-house artist emulating Neill’s style.

As for Neill potentially drawing the revised illustration himself, while the image is a close copy, Neill’s grand-daughter, Jory Mason, herself an accomplished artist, is quick to point out, “In my opinion, the illustration does not look like his line work.” The revision also lack’s Neill’s signature from the original – likely another tell-tale sign it was instead the work of a skilled in-house artist emulating Neill’s style.

But perhaps most persuasively, there is no record, either in the publisher’s files or Neill’s family papers of Neill ever having been paid to modify any of his illustrations for the Oz book series – either by redrawing them (or in the instance of other found works – by embellishing pen and ink drawings with watercolor to make them more suitable for advertising re-purpose). Lest we forget, for much of Neill’s career, illustrating the Oz books was simply ‘a gig’ – one of many that the industrious Neill took on each month in his career as a working illustrator. It’s unlikely he would have taken on the extra assignment without further compensation. Neill, after all, had no idea in 1904 or 1918 of what “Oz” would eventually come to mean as an enduring, decades long American phenom…

Only in 1941 – decades later – did Neill write, “I’m beginning, after about 40 years,” to realize there is more to this Oz stuff than I thought.” As it would happen, the line was written to Jack Snow, who would end up adding a faux drawing to his own collection, perhaps one of the first prized as a Neill original.

Special thanks to Michael Patrick Hearn, Jory Mason, Penny White, and the University of Virginia for their expertise.